Black pepper vine (left), ripening fruit (centre) and dried peppercorns (right).

Black pepper vine (left), ripening fruit (centre) and dried peppercorns (right).

Welcome to the FabulousFusionFood page for the history of the global spread of Black Pepper as a spice. Here you will how Black Pepper spread out from its original home in India to be grown and traded around the world. You will also learn why black pepper remains the world's most traded spice.

Please note that this recipe page (and all the other recipe pages on this site) are brought to you in association with the 'One Million People' campaign, which attempts to make available a number of ancient texts (particularly those relating to recipes) available for free on this site.

This page is presented as part of my 'History of the Spice Trade' section of the FabulousFusionFood Recipes site. You can use the table below to navigate the various sections of this history:

Introduction

Fig 1: The different types of peppercorn derived from black pepper. These are black peppercorns and white peppercorns (top); green peppercorns and pickled green peppercorns (centre) and dried red peppercorns and preserved red peppercorns (bottom).

Fig 1: The different types of peppercorn derived from black pepper. These are black peppercorns and white peppercorns (top); green peppercorns and pickled green peppercorns (centre) and dried red peppercorns and preserved red peppercorns (bottom).

Black pepper has been called the 'king of spices' as it provides warming heat and spiciness with no bitterness. Its only rival in this being the chilli pepper. However, capsaicin, the chemical responsible for the heat of chillies is 10 times stronger than piperine, the heat chemical in black pepper. Today, in the West at least, black pepper is a common table condiment. Black pepper also remains the world's most traded spice.

Arguably the quest for pepper's spiciness has led to the development of trade routes and the exploration of the globe. Which is why, black pepper is getting its own page on this site. Pepper is also the definitive hot spice and other hot spices have been compared to black pepper and used as substitutes (cf black pepper, cubeb pepper, alligator pepper, pink peppercorns, etc.).

Peppercorns are the processed drupes (fruit) of the black pepper vine, Piper nigrum and come in a variety of colours: black, green, white, red; depending on the level of ripeness and degree of processing of the fruit.

Black Pepper

Black pepper is produced from the still-green, unripe drupe of the pepper plant. The drupes are cooked briefly in hot water, both to clean them and to prepare them for drying. The heat ruptures cell walls in the pepper, speeding the work of browning enzymes during drying.[9] The drupes dry in the sun or by machine for several days, during which the pepper skin around the seed shrinks and darkens into a thin, wrinkled black layer. Once dry, the spice is called black peppercorn. On some estates, the berries are separated from the stem by hand and then sun-dried without boiling.

After the peppercorns are dried, pepper spirit and oil can be extracted from the berries by crushing them. Pepper spirit is used in many medicinal and beauty products. Pepper oil is also used as an ayurvedic massage oil and in certain beauty and herbal treatments.

White pepper

White pepper consists solely of the seed of the ripe fruit of the pepper plant, with the thin darker-coloured skin (flesh) of the fruit removed. This is usually accomplished by a process known as retting, where fully ripe red pepper berries are soaked in water for about a week so the flesh of the peppercorn softens and decomposes; rubbing then removes what remains of the fruit, and the naked seed is dried. Sometimes the outer layer is removed from the seed through other mechanical, chemical, or biological methods.

Ground white pepper is commonly used in Chinese, Thai, and Portuguese cuisines. It finds occasional use in other cuisines in salads, light-coloured sauces, and mashed potatoes as a substitute for black pepper, because black pepper would visibly stand out. However, white pepper lacks certain compounds present in the outer layer of the drupe, resulting in a different overall flavour.

Green pepper

Green pepper, like black pepper, is made from unripe drupes. Dried green peppercorns are treated in a way that retains the green colour, such as with sulphur dioxide, canning, or freeze-drying. Pickled peppercorns, also green, are unripe drupes preserved in brine or vinegar.

Fresh, unpreserved green pepper drupes are used in some cuisines like Thai cuisine and Tamil cuisine. Their flavour has been described as 'spicy and fresh', with a 'bright aroma.' They decay quickly if not dried or preserved, making them unsuitable for international shipping.

Red peppercorns

Red peppercorns usually consist of ripe peppercorn drupes preserved in brine and vinegar. Ripe red peppercorns can also be dried using the same colour-preserving techniques used to produce green pepper.

Black pepper is native to the Malabar Coast of India, and the Malabar pepper is extensively cultivated there and in other tropical regions.

The pepper plant is a perennial woody vine growing up to 4m in height on supporting trees, poles, or trellises. It is a spreading vine, rooting readily where trailing stems touch the ground. The leaves are alternate, entire, 5 to 10 cm long and 3 to 6 cm across. The flowers are small, produced on pendulous spikes 4 to 8 cm long at the leaf nodes, the spikes lengthening up to 7 to 15 cm as the fruit matures.

Pepper can be grown in soil that is neither too dry nor susceptible to flooding, moist, well-drained, and rich in organic matter (the vines do not do well over an altitude of 900 m above sea level). The plants are propagated by cuttings about 40 to 50 cm long, tied up to neighbouring trees or climbing frames at distances of about 2 m apart; trees with rough bark are favoured over those with smooth bark, as the pepper plants climb rough bark more readily. Competing plants are cleared away, leaving only sufficient trees to provide shade and permit free ventilation. The roots are covered in leaf mulch and manure, and the shoots are trimmed twice a year. On dry soils, the young plants require watering every other day during the dry season for the first three years. The plants bear fruit from the fourth or fifth year, and then typically for seven years. The cuttings are usually cultivars, selected both for yield and quality of fruit.

A single stem bears 20 to 30 fruiting spikes. The harvest begins as soon as one or two fruits at the base of the spikes begin to turn red, and before the fruit is fully mature, and still hard; if allowed to ripen completely, the fruits lose pungency, and ultimately fall off and are lost. The spikes are collected and spread out to dry in the sun, then the peppercorns are stripped off the spikes.

Black pepper is native either to Southeast Asia or South Asia. Within the genus Piper, it is most closely related to other Asian species such as P. caninum (dog pepper).

Wild pepper grows in the Western Ghats region of India. Into the 19th century, the forests contained expansive wild pepper vines, as recorded by the Scottish physician Francis Buchanan (also a botanist and geographer) in his book A journey from Madras through the countries of Mysore, Canara and Malabar (Volume III). However, deforestation resulted in wild pepper growing in more limited forest patches from Goa to Kerala, with the wild source gradually decreasing as the quality and yield of the cultivated variety improved. No successful grafting of commercial pepper on wild pepper has been achieved to date. Here, Voatsiperifery Pepper also needs to be mentioned. These are the drupes of Piper borbonense a close relative of Piper nigrum that grows wild in Madagascar and which is collected like black pepper; this plant has not been domesticated.

In 2020, Vietnam was the world's largest producer and exporter of black peppercorns, producing 270,192 tonnes or 36% of the world total (table). Other major producers were Brazil, Indonesia, India, Sri Lanka, China, and Malaysia. Global pepper production varies annually according to crop management, disease, and weather. Peppercorns are among the most widely traded spice in the world, accounting for 20% of all spice imports.

The ancient history of black pepper is often interlinked with (and confused with) that of long pepper, the dried fruit of closely related Piper longum. The Romans knew of both and often referred to either as just piper. In fact, the popularity of long pepper did not entirely decline until the discovery of the New World and of chilli peppers. Chilli peppers—some of which, when dried, are similar in shape and taste to long pepper—were easier to grow in a variety of locations more convenient to Europe. Before the 16th century, pepper was being grown in Java, Sunda, Sumatra, Madagascar, Malaysia, and everywhere in Southeast Asia. These areas traded mainly with China, or used the pepper locally. Ports in the Malabar area also served as a stop-off point for much of the trade in other spices from farther east in the Indian Ocean.

It should be noted that by 100 BCE there was an extensive spice route connecting the main spice trading ports to Arabia and Europe. This was first established by Indian traders.

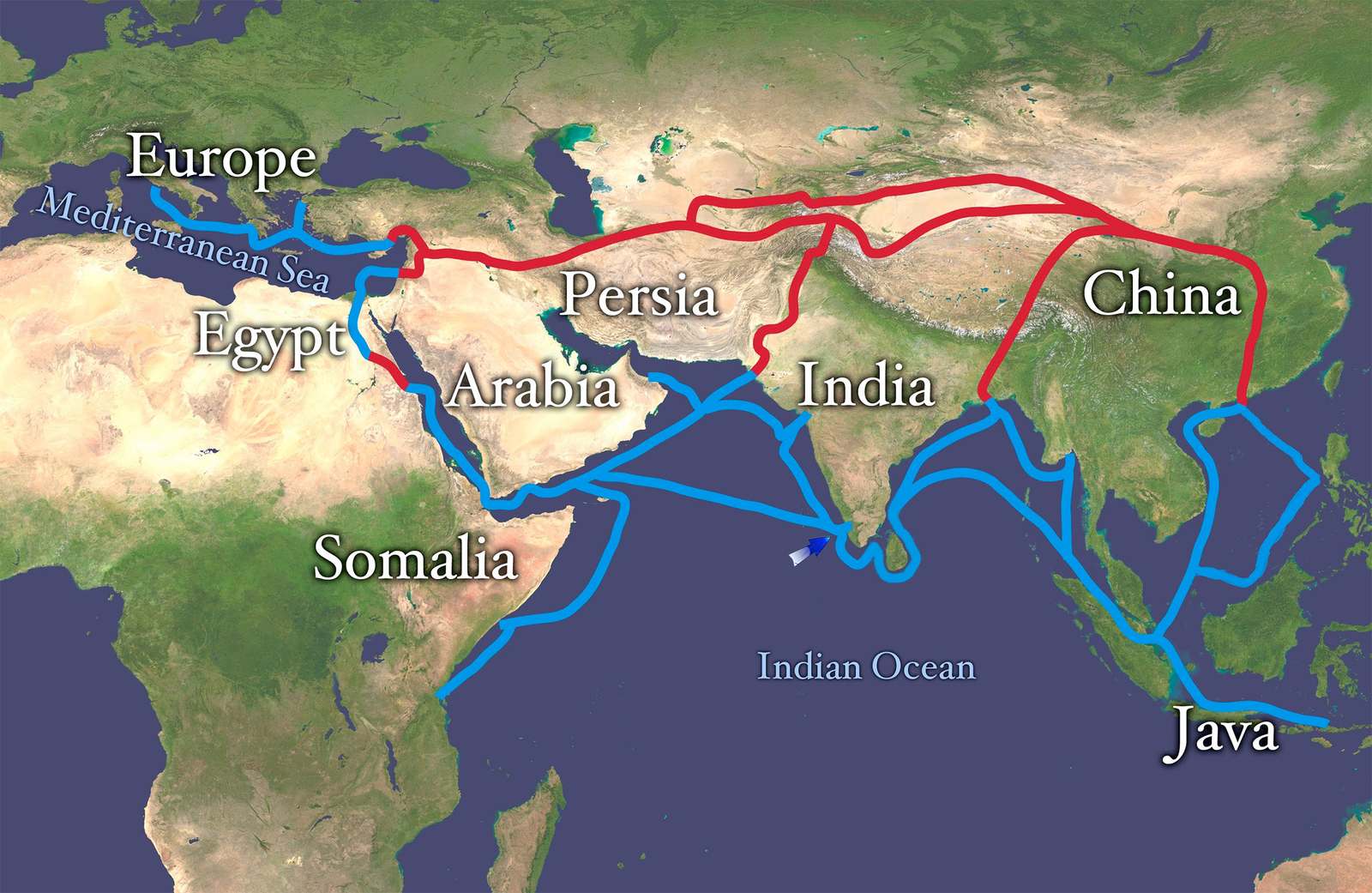

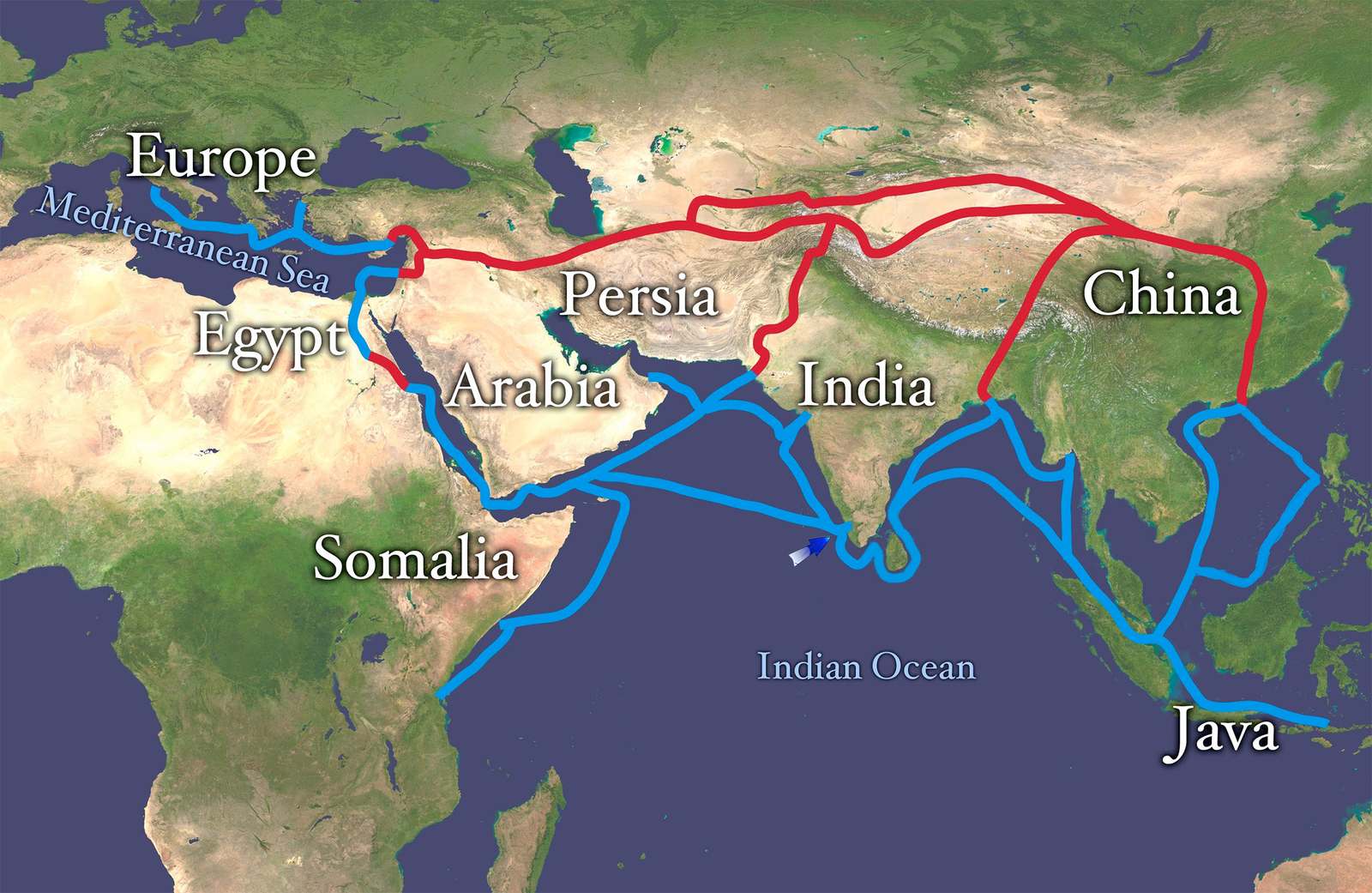

Fig 2: The image above shows the ancient trading routes of the Old World. The Silk Road (shown in red) is probably the most well know, however, there was a parallel sea-based spice route (shown in blue). One of the most important stopping points for this naval trade route was off the Malabar coast of India (shown with an arrow) which allowed for unloading of other spices, but for also allowed for the loading of black pepper to be transported elsewhere in India and then Westwards to Arabia, the horn of Africa and Europe. And, of course, Eastwards to Thailand, Java, China and Japan. This sea-based route also connected with the silk road, allowing even more widespread dissemination of spices.

Fig 2: The image above shows the ancient trading routes of the Old World. The Silk Road (shown in red) is probably the most well know, however, there was a parallel sea-based spice route (shown in blue). One of the most important stopping points for this naval trade route was off the Malabar coast of India (shown with an arrow) which allowed for unloading of other spices, but for also allowed for the loading of black pepper to be transported elsewhere in India and then Westwards to Arabia, the horn of Africa and Europe. And, of course, Eastwards to Thailand, Java, China and Japan. This sea-based route also connected with the silk road, allowing even more widespread dissemination of spices.

Pepper (both long and black) was known in Greece at least as early as the fourth century BCE, though it was probably an uncommon and expensive item that only the very rich could afford.

By the time of the early Roman Empire, especially after Rome's conquest of Egypt in 30 BCE, open-ocean crossing of the Arabian Sea direct to Chera dynasty southern India's Malabar Coast was near routine. Details of this trading across the Indian Ocean have been passed down in the Periplus of the Erythraean Sea. According to the Greek geographer Strabo, the early empire sent a fleet of around 120 ships on an annual trip to India and back.[28] The fleet timed its travel across the Arabian Sea to take advantage of the predictable monsoon winds. Returning from India, the ships travelled up the Red Sea, from where the cargo was carried overland or via the Nile-Red Sea canal to the Nile River, barged to Alexandria, and shipped from there to Italy and Rome. The rough geographical outlines of this same trade route would dominate the pepper trade into Europe for a millennium and a half to come.

Fig 3: The route for black pepper into Rome. This is a marine route from the Malabar coast in India, across land in Egypt then a maritime route to Crete (and thence Greece) with a second leg to Palermo and Rome..

Fig 3: The route for black pepper into Rome. This is a marine route from the Malabar coast in India, across land in Egypt then a maritime route to Crete (and thence Greece) with a second leg to Palermo and Rome..

With ships sailing directly to the Malabar coast, Malabar black pepper was now travelling a shorter trade route than long pepper, and the prices reflected it. Pliny the Elder's Natural History tells us the prices in Rome around 77 CE: "Long pepper ... is 15 denarii per pound, while that of white pepper is seven, and of black, four." Pliny also complains, "There is no year in which India does not drain the Roman Empire of 50 million sesterces", and further moralizes on pepper:

He does not state whether the 50 million was the actual amount of money which found its way to India or the total retail cost of the items in Rome, and, elsewhere, he cites a figure of 100 million sesterces.

Black pepper was a well-known and widespread, if expensive, seasoning in the Roman Empire. Apicius' De re coquinaria, a third-century cookbook probably based at least partly on one from the first century CE, includes pepper in a majority of its recipes. Edward Gibbon wrote, in The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, that pepper was 'a favourite ingredient of the most expensive Roman cookery'

A riddle authored by Saint Aldhelm, a seventh-century Bishop of Sherborne, sheds some light on black pepper's role in England at that time:

I am black on the outside, clad in a wrinkled cover,

Yet within I bear a burning marrow.

I season delicacies, the banquets of kings, and the luxuries of the table,

Both the sauces and the tenderized meats of the kitchen.

But you will find in me no quality of any worth,

Unless your bowels have been rattled by my gleaming marrow.

It is commonly believed that during the Middle Ages, pepper was often used to conceal the taste of partially rotten meat. No evidence supports this claim, and historians view it as highly unlikely; in the Middle Ages, pepper was a luxury item, affordable only to the wealthy, who certainly had unspoiled meat available, as well.[34] In addition, people of the time certainly knew that eating spoiled food would make them sick. Similarly, the belief that pepper was widely used as a preservative is questionable; it is true that piperine, the compound that gives pepper its spiciness, has some antimicrobial properties, but at the concentrations present when pepper is used as a spice, the effect is small. Salt is a much more effective preservative, and salt-cured meats were common fare, especially in winter. However, pepper and other spices certainly played a role in improving the taste of long-preserved meats.

Its exorbitant price during the Middle Ages – and the monopoly on the trade held by Venice – was one of the inducements that led the Portuguese to seek a sea route to India. In 1498, Vasco da Gama became the first person to reach India by sailing around Africa (see Age of Discovery); asked by Arabs in Calicut (who spoke Spanish and Italian) why they had come, his representative replied, "we seek Christians and spices".[36] Though this first trip to India by way of the southern tip of Africa was only a modest success, the Portuguese quickly returned in greater numbers and eventually gained much greater control of trade on the Arabian Sea. The 1494 Treaty of Tordesillas with the Spanish granted Portugal exclusive rights to the half of the world where black pepper originated.

However, the Portuguese proved unable to monopolize the spice trade. Older Arab and Venetian trade networks successfully imported enormous quantities of spices, and pepper once again flowed through Alexandria and Italy, as well as around Africa. In the 17th century, the Portuguese lost almost all of their valuable Indian Ocean trade to the Dutch and the English, who, taking advantage of the Spanish rule over Portugal during the Iberian Union (1580–1640), occupied by force almost all Portuguese interests in the area. The pepper ports of Malabar began to trade increasingly with the Dutch in the period 1661–1663.

As pepper supplies into Europe increased, the price of pepper declined (though the total value of the import trade generally did not). Pepper, which in the early Middle Ages had been an item exclusively for the rich, started to become more of an everyday seasoning among those of more average means. Today, pepper accounts for one-fifth of the world's spice trade.

The English word 'pepper' derives from Old English pipor a loanword from the Latin piper and and Greek: πέπερι. Both of these are derived from the Dravidian pippali, meaning "long pepper" which shares a common root with Sanskrit pippali. It should be noted that the Hindi word for black pepper is kali mirch or kalimirch.

Due to its botanic origins it's hardly surprising that black pepper first became an important ingredient in South Indian cuisine and it remains a key spice in many South Indian dishes to this day. However, for the spread of black pepper throughout the cuisines of India as a whole we probably have to turn towards the influence of Ayurveda.

Ayurveda is an alternative medicine system with historical roots in the Indian subcontinent. It is heavily practiced in India and Nepal, where around 80% of the population report using ayurveda.

The origins of Ayurveda remain mysterious, though most scholars tend to agree that the main tenets were laid down between 500 BCE and 500 CE. In Ayurveda black pepper is believed to have cleansing and antioxidant properties. It is also a bioavailability enhancer; it helps transport the benefits of other herbs to the different parts of the body. Black pepper is also believed to support the free flow of oxygen to the brain, helps enhance digestion and circulation, stimulates the appetite, and helps maintain respiratory system health and the health of the joints.

As Ayurvedic cooking became more common and black pepper was increasingly added to the diet. This probably explains the addition of black pepper to garam masala, which has become an ubiquitous household spice mixture used throughout Indian cookery. This also lead to the general liking for pepperiness in Indian cookery which helps explain why chillies were so readily adapted as the main hot spice once introduced by the Portuguese.

Few Indian dishes, today, are spiced with black pepper alone, one of the exceptions being Chicken Kali Mirch (Black Pepper Chicken Curry).

In the third century CE, black pepper made its first definite appearance in Chinese texts, as hujiao or "foreign pepper". It does not appear to have been widely known at the time, failing to appear in a fourth-century work describing a wide variety of spices from beyond China's southern border, including long pepper. By the 12th century, however, black pepper had become a popular ingredient in the cuisine of the wealthy and powerful, sometimes taking the place of China's native Sichuan pepper (the tongue-numbing dried fruit of an unrelated plant).

Marco Polo testifies to pepper's popularity in 13th-century China, when he relates what he is told of its consumption in the city of Kinsay (Hangzhou): "... Messer Marco heard it stated by one of the Great Kaan's officers of customs that the quantity of pepper introduced daily for consumption into the city of Kinsay amounted to 43 loads, each load being equal to 223 lbs."

During the course of the Ming treasure voyages in the early 15th century, Admiral Zheng He and his expeditionary fleets returned with such a large amount of black pepper that the once-costly luxury became a common commodity.

For more information about the use of Black Pepper as a spice and a link to saffron-based recipes, see this site's Spice Guide page for Black Pepper

Please note that this recipe page (and all the other recipe pages on this site) are brought to you in association with the 'One Million People' campaign, which attempts to make available a number of ancient texts (particularly those relating to recipes) available for free on this site.

This page is presented as part of my 'History of the Spice Trade' section of the FabulousFusionFood Recipes site. You can use the table below to navigate the various sections of this history:

FabulousFusionFood History of the Spread of Black Pepper around the Globe

Introduction

Fig 1: The different types of peppercorn derived from black pepper. These are black peppercorns and white peppercorns (top); green peppercorns and pickled green peppercorns (centre) and dried red peppercorns and preserved red peppercorns (bottom).

Fig 1: The different types of peppercorn derived from black pepper. These are black peppercorns and white peppercorns (top); green peppercorns and pickled green peppercorns (centre) and dried red peppercorns and preserved red peppercorns (bottom).

Black pepper has been called the 'king of spices' as it provides warming heat and spiciness with no bitterness. Its only rival in this being the chilli pepper. However, capsaicin, the chemical responsible for the heat of chillies is 10 times stronger than piperine, the heat chemical in black pepper. Today, in the West at least, black pepper is a common table condiment. Black pepper also remains the world's most traded spice.

Arguably the quest for pepper's spiciness has led to the development of trade routes and the exploration of the globe. Which is why, black pepper is getting its own page on this site. Pepper is also the definitive hot spice and other hot spices have been compared to black pepper and used as substitutes (cf black pepper, cubeb pepper, alligator pepper, pink peppercorns, etc.).

Peppercorns are the processed drupes (fruit) of the black pepper vine, Piper nigrum and come in a variety of colours: black, green, white, red; depending on the level of ripeness and degree of processing of the fruit.

Black Pepper

Black pepper is produced from the still-green, unripe drupe of the pepper plant. The drupes are cooked briefly in hot water, both to clean them and to prepare them for drying. The heat ruptures cell walls in the pepper, speeding the work of browning enzymes during drying.[9] The drupes dry in the sun or by machine for several days, during which the pepper skin around the seed shrinks and darkens into a thin, wrinkled black layer. Once dry, the spice is called black peppercorn. On some estates, the berries are separated from the stem by hand and then sun-dried without boiling.

After the peppercorns are dried, pepper spirit and oil can be extracted from the berries by crushing them. Pepper spirit is used in many medicinal and beauty products. Pepper oil is also used as an ayurvedic massage oil and in certain beauty and herbal treatments.

White pepper

White pepper consists solely of the seed of the ripe fruit of the pepper plant, with the thin darker-coloured skin (flesh) of the fruit removed. This is usually accomplished by a process known as retting, where fully ripe red pepper berries are soaked in water for about a week so the flesh of the peppercorn softens and decomposes; rubbing then removes what remains of the fruit, and the naked seed is dried. Sometimes the outer layer is removed from the seed through other mechanical, chemical, or biological methods.

Ground white pepper is commonly used in Chinese, Thai, and Portuguese cuisines. It finds occasional use in other cuisines in salads, light-coloured sauces, and mashed potatoes as a substitute for black pepper, because black pepper would visibly stand out. However, white pepper lacks certain compounds present in the outer layer of the drupe, resulting in a different overall flavour.

Green pepper

Green pepper, like black pepper, is made from unripe drupes. Dried green peppercorns are treated in a way that retains the green colour, such as with sulphur dioxide, canning, or freeze-drying. Pickled peppercorns, also green, are unripe drupes preserved in brine or vinegar.

Fresh, unpreserved green pepper drupes are used in some cuisines like Thai cuisine and Tamil cuisine. Their flavour has been described as 'spicy and fresh', with a 'bright aroma.' They decay quickly if not dried or preserved, making them unsuitable for international shipping.

Red peppercorns

Red peppercorns usually consist of ripe peppercorn drupes preserved in brine and vinegar. Ripe red peppercorns can also be dried using the same colour-preserving techniques used to produce green pepper.

The Pepper Plant

Botanically, black pepper (Piper nigrum) is a flowering vine in the family Piperaceae, cultivated for its fruit (the peppercorn), which is usually dried and used as a spice and seasoning. The fruit is a drupe (stonefruit) which is about 5mm in diameter (fresh and fully mature), dark red, and contains a stone which encloses a single pepper seed. Peppercorns and the ground pepper derived from them may be described simply as pepper, or more precisely as black pepper (cooked and dried unripe fruit), green pepper (dried unripe fruit), or white pepper (ripe fruit seeds).Black pepper is native to the Malabar Coast of India, and the Malabar pepper is extensively cultivated there and in other tropical regions.

The pepper plant is a perennial woody vine growing up to 4m in height on supporting trees, poles, or trellises. It is a spreading vine, rooting readily where trailing stems touch the ground. The leaves are alternate, entire, 5 to 10 cm long and 3 to 6 cm across. The flowers are small, produced on pendulous spikes 4 to 8 cm long at the leaf nodes, the spikes lengthening up to 7 to 15 cm as the fruit matures.

Pepper can be grown in soil that is neither too dry nor susceptible to flooding, moist, well-drained, and rich in organic matter (the vines do not do well over an altitude of 900 m above sea level). The plants are propagated by cuttings about 40 to 50 cm long, tied up to neighbouring trees or climbing frames at distances of about 2 m apart; trees with rough bark are favoured over those with smooth bark, as the pepper plants climb rough bark more readily. Competing plants are cleared away, leaving only sufficient trees to provide shade and permit free ventilation. The roots are covered in leaf mulch and manure, and the shoots are trimmed twice a year. On dry soils, the young plants require watering every other day during the dry season for the first three years. The plants bear fruit from the fourth or fifth year, and then typically for seven years. The cuttings are usually cultivars, selected both for yield and quality of fruit.

A single stem bears 20 to 30 fruiting spikes. The harvest begins as soon as one or two fruits at the base of the spikes begin to turn red, and before the fruit is fully mature, and still hard; if allowed to ripen completely, the fruits lose pungency, and ultimately fall off and are lost. The spikes are collected and spread out to dry in the sun, then the peppercorns are stripped off the spikes.

Black pepper is native either to Southeast Asia or South Asia. Within the genus Piper, it is most closely related to other Asian species such as P. caninum (dog pepper).

Wild pepper grows in the Western Ghats region of India. Into the 19th century, the forests contained expansive wild pepper vines, as recorded by the Scottish physician Francis Buchanan (also a botanist and geographer) in his book A journey from Madras through the countries of Mysore, Canara and Malabar (Volume III). However, deforestation resulted in wild pepper growing in more limited forest patches from Goa to Kerala, with the wild source gradually decreasing as the quality and yield of the cultivated variety improved. No successful grafting of commercial pepper on wild pepper has been achieved to date. Here, Voatsiperifery Pepper also needs to be mentioned. These are the drupes of Piper borbonense a close relative of Piper nigrum that grows wild in Madagascar and which is collected like black pepper; this plant has not been domesticated.

In 2020, Vietnam was the world's largest producer and exporter of black peppercorns, producing 270,192 tonnes or 36% of the world total (table). Other major producers were Brazil, Indonesia, India, Sri Lanka, China, and Malaysia. Global pepper production varies annually according to crop management, disease, and weather. Peppercorns are among the most widely traded spice in the world, accounting for 20% of all spice imports.

Black Pepper and the Spice Trade

Black pepper is native to South Asia and Southeast Asia, and has been known to Indian cooking since at least 2000 BCE.[20][how?] J. Innes Miller notes that while pepper was grown in southern Thailand and in Malaysia,[when?] its most important source was India, particularly the Malabar Coast, in what is now the state of Kerala. The lost ancient port city of Muziris in Kerala, famous for exporting black pepper and various other spices, gets mentioned in a number of classical historical sources for its trade with Roman Empire, Egypt, Mesopotamia, Levant, and Yemen. Peppercorns were a much-prized trade good, often referred to as "black gold" and used as a form of commodity money. The legacy of this trade remains in some Western legal systems that recognize the term "peppercorn rent" as a token payment for something that is, essentially, a gift.The ancient history of black pepper is often interlinked with (and confused with) that of long pepper, the dried fruit of closely related Piper longum. The Romans knew of both and often referred to either as just piper. In fact, the popularity of long pepper did not entirely decline until the discovery of the New World and of chilli peppers. Chilli peppers—some of which, when dried, are similar in shape and taste to long pepper—were easier to grow in a variety of locations more convenient to Europe. Before the 16th century, pepper was being grown in Java, Sunda, Sumatra, Madagascar, Malaysia, and everywhere in Southeast Asia. These areas traded mainly with China, or used the pepper locally. Ports in the Malabar area also served as a stop-off point for much of the trade in other spices from farther east in the Indian Ocean.

It should be noted that by 100 BCE there was an extensive spice route connecting the main spice trading ports to Arabia and Europe. This was first established by Indian traders.

Fig 2: The image above shows the ancient trading routes of the Old World. The Silk Road (shown in red) is probably the most well know, however, there was a parallel sea-based spice route (shown in blue). One of the most important stopping points for this naval trade route was off the Malabar coast of India (shown with an arrow) which allowed for unloading of other spices, but for also allowed for the loading of black pepper to be transported elsewhere in India and then Westwards to Arabia, the horn of Africa and Europe. And, of course, Eastwards to Thailand, Java, China and Japan. This sea-based route also connected with the silk road, allowing even more widespread dissemination of spices.

Fig 2: The image above shows the ancient trading routes of the Old World. The Silk Road (shown in red) is probably the most well know, however, there was a parallel sea-based spice route (shown in blue). One of the most important stopping points for this naval trade route was off the Malabar coast of India (shown with an arrow) which allowed for unloading of other spices, but for also allowed for the loading of black pepper to be transported elsewhere in India and then Westwards to Arabia, the horn of Africa and Europe. And, of course, Eastwards to Thailand, Java, China and Japan. This sea-based route also connected with the silk road, allowing even more widespread dissemination of spices.

The Classical Era

Black peppercorns were found stuffed in the nostrils of Ramesses II, placed there as part of the mummification rituals shortly after his death in 1213 BCE. Little else is known about the use of pepper in ancient Egypt and how it reached the Nile from the Malabar Coast of South India.Pepper (both long and black) was known in Greece at least as early as the fourth century BCE, though it was probably an uncommon and expensive item that only the very rich could afford.

By the time of the early Roman Empire, especially after Rome's conquest of Egypt in 30 BCE, open-ocean crossing of the Arabian Sea direct to Chera dynasty southern India's Malabar Coast was near routine. Details of this trading across the Indian Ocean have been passed down in the Periplus of the Erythraean Sea. According to the Greek geographer Strabo, the early empire sent a fleet of around 120 ships on an annual trip to India and back.[28] The fleet timed its travel across the Arabian Sea to take advantage of the predictable monsoon winds. Returning from India, the ships travelled up the Red Sea, from where the cargo was carried overland or via the Nile-Red Sea canal to the Nile River, barged to Alexandria, and shipped from there to Italy and Rome. The rough geographical outlines of this same trade route would dominate the pepper trade into Europe for a millennium and a half to come.

Fig 3: The route for black pepper into Rome. This is a marine route from the Malabar coast in India, across land in Egypt then a maritime route to Crete (and thence Greece) with a second leg to Palermo and Rome..

Fig 3: The route for black pepper into Rome. This is a marine route from the Malabar coast in India, across land in Egypt then a maritime route to Crete (and thence Greece) with a second leg to Palermo and Rome..

With ships sailing directly to the Malabar coast, Malabar black pepper was now travelling a shorter trade route than long pepper, and the prices reflected it. Pliny the Elder's Natural History tells us the prices in Rome around 77 CE: "Long pepper ... is 15 denarii per pound, while that of white pepper is seven, and of black, four." Pliny also complains, "There is no year in which India does not drain the Roman Empire of 50 million sesterces", and further moralizes on pepper:

It is quite surprising that the use of pepper has come so much into fashion, seeing that in other substances which we use, it is sometimes their sweetness, and sometimes their appearance that has attracted our notice; whereas, pepper has nothing in it that can plead as a recommendation to either fruit or berry, its only desirable quality being a certain pungency; and yet it is for this that we import it all the way from India! Who was the first to make trial of it as an article of food? and who, I wonder, was the man that was not content to prepare himself by hunger only for the satisfying of a greedy appetite?

— Pliny, Natural History 12.14

He does not state whether the 50 million was the actual amount of money which found its way to India or the total retail cost of the items in Rome, and, elsewhere, he cites a figure of 100 million sesterces.

Black pepper was a well-known and widespread, if expensive, seasoning in the Roman Empire. Apicius' De re coquinaria, a third-century cookbook probably based at least partly on one from the first century CE, includes pepper in a majority of its recipes. Edward Gibbon wrote, in The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, that pepper was 'a favourite ingredient of the most expensive Roman cookery'

Post Classical to Late Middle Age Europe

Pepper was so valuable that it was often used as collateral or even currency. The taste for pepper (or the appreciation of its monetary value) was passed on to those who would see Rome fall. Alaric, king of the Visigoths, included 3,000 pounds of pepper as part of the ransom he demanded from Rome when he besieged the city in the fifth century.[31] After the fall of Rome, others took over the middle legs of the spice trade, first the Persians and then the Arabs; Innes Miller cites the account of Cosmas Indicopleustes, who travelled east to India, as proof that "pepper was still being exported from India in the sixth century". By the end of the Early Middle Ages, the central portions of the spice trade were firmly under Islamic control. Once into the Mediterranean, the trade was largely monopolized by Italian powers, especially Venice and Genoa. The rise of these city-states was funded in large part by the spice trade.A riddle authored by Saint Aldhelm, a seventh-century Bishop of Sherborne, sheds some light on black pepper's role in England at that time:

I am black on the outside, clad in a wrinkled cover,

Yet within I bear a burning marrow.

I season delicacies, the banquets of kings, and the luxuries of the table,

Both the sauces and the tenderized meats of the kitchen.

But you will find in me no quality of any worth,

Unless your bowels have been rattled by my gleaming marrow.

It is commonly believed that during the Middle Ages, pepper was often used to conceal the taste of partially rotten meat. No evidence supports this claim, and historians view it as highly unlikely; in the Middle Ages, pepper was a luxury item, affordable only to the wealthy, who certainly had unspoiled meat available, as well.[34] In addition, people of the time certainly knew that eating spoiled food would make them sick. Similarly, the belief that pepper was widely used as a preservative is questionable; it is true that piperine, the compound that gives pepper its spiciness, has some antimicrobial properties, but at the concentrations present when pepper is used as a spice, the effect is small. Salt is a much more effective preservative, and salt-cured meats were common fare, especially in winter. However, pepper and other spices certainly played a role in improving the taste of long-preserved meats.

Its exorbitant price during the Middle Ages – and the monopoly on the trade held by Venice – was one of the inducements that led the Portuguese to seek a sea route to India. In 1498, Vasco da Gama became the first person to reach India by sailing around Africa (see Age of Discovery); asked by Arabs in Calicut (who spoke Spanish and Italian) why they had come, his representative replied, "we seek Christians and spices".[36] Though this first trip to India by way of the southern tip of Africa was only a modest success, the Portuguese quickly returned in greater numbers and eventually gained much greater control of trade on the Arabian Sea. The 1494 Treaty of Tordesillas with the Spanish granted Portugal exclusive rights to the half of the world where black pepper originated.

However, the Portuguese proved unable to monopolize the spice trade. Older Arab and Venetian trade networks successfully imported enormous quantities of spices, and pepper once again flowed through Alexandria and Italy, as well as around Africa. In the 17th century, the Portuguese lost almost all of their valuable Indian Ocean trade to the Dutch and the English, who, taking advantage of the Spanish rule over Portugal during the Iberian Union (1580–1640), occupied by force almost all Portuguese interests in the area. The pepper ports of Malabar began to trade increasingly with the Dutch in the period 1661–1663.

As pepper supplies into Europe increased, the price of pepper declined (though the total value of the import trade generally did not). Pepper, which in the early Middle Ages had been an item exclusively for the rich, started to become more of an everyday seasoning among those of more average means. Today, pepper accounts for one-fifth of the world's spice trade.

India

It should be noted that black pepper is native only to the Malabar coast of India and not to the sub-continent as a whole. Indeed, the original reconstructed Indian curry (from the Harappan culture) had no black pepper in it. Nor did the first curries that were exported from India to Vietnam. It was only with the development of Garam Masala (which always has black pepper) as a key flavouring and chaat masala as a condiment added after cooking that black pepper became more ubiquitous. Today, black pepper is fairly common in Indian and Bengali cuisines, though when black pepper became an ubiquitous spice in Indian cookery is harder to pin down.The English word 'pepper' derives from Old English pipor a loanword from the Latin piper and and Greek: πέπερι. Both of these are derived from the Dravidian pippali, meaning "long pepper" which shares a common root with Sanskrit pippali. It should be noted that the Hindi word for black pepper is kali mirch or kalimirch.

Due to its botanic origins it's hardly surprising that black pepper first became an important ingredient in South Indian cuisine and it remains a key spice in many South Indian dishes to this day. However, for the spread of black pepper throughout the cuisines of India as a whole we probably have to turn towards the influence of Ayurveda.

Ayurveda is an alternative medicine system with historical roots in the Indian subcontinent. It is heavily practiced in India and Nepal, where around 80% of the population report using ayurveda.

The origins of Ayurveda remain mysterious, though most scholars tend to agree that the main tenets were laid down between 500 BCE and 500 CE. In Ayurveda black pepper is believed to have cleansing and antioxidant properties. It is also a bioavailability enhancer; it helps transport the benefits of other herbs to the different parts of the body. Black pepper is also believed to support the free flow of oxygen to the brain, helps enhance digestion and circulation, stimulates the appetite, and helps maintain respiratory system health and the health of the joints.

As Ayurvedic cooking became more common and black pepper was increasingly added to the diet. This probably explains the addition of black pepper to garam masala, which has become an ubiquitous household spice mixture used throughout Indian cookery. This also lead to the general liking for pepperiness in Indian cookery which helps explain why chillies were so readily adapted as the main hot spice once introduced by the Portuguese.

Few Indian dishes, today, are spiced with black pepper alone, one of the exceptions being Chicken Kali Mirch (Black Pepper Chicken Curry).

China

It is possible that black pepper was known in China in the second century BCE, if poetic reports regarding an explorer named Tang Meng (唐蒙) are correct. Sent by Emperor Wu to what is now south-west China, Tang Meng is said to have come across something called jujiang or "sauce-betel". He was told it came from the markets of Shu, an area in what is now the Sichuan province. The traditional view among historians is that "sauce-betel" is a sauce made from betel leaves, but arguments have been made that it actually refers to pepper, either long or black.In the third century CE, black pepper made its first definite appearance in Chinese texts, as hujiao or "foreign pepper". It does not appear to have been widely known at the time, failing to appear in a fourth-century work describing a wide variety of spices from beyond China's southern border, including long pepper. By the 12th century, however, black pepper had become a popular ingredient in the cuisine of the wealthy and powerful, sometimes taking the place of China's native Sichuan pepper (the tongue-numbing dried fruit of an unrelated plant).

Marco Polo testifies to pepper's popularity in 13th-century China, when he relates what he is told of its consumption in the city of Kinsay (Hangzhou): "... Messer Marco heard it stated by one of the Great Kaan's officers of customs that the quantity of pepper introduced daily for consumption into the city of Kinsay amounted to 43 loads, each load being equal to 223 lbs."

During the course of the Ming treasure voyages in the early 15th century, Admiral Zheng He and his expeditionary fleets returned with such a large amount of black pepper that the once-costly luxury became a common commodity.

For more information about the use of Black Pepper as a spice and a link to saffron-based recipes, see this site's Spice Guide page for Black Pepper