A mixture of spices shown in bowls that feature in this guide.

A mixture of spices shown in bowls that feature in this guide.

Welcome to the Celtnet Recipes page for the History of the Spice Trade. This first page, in a series of articles, gives you an introduction to what spices are and tells you about the origins of the spice trade in the Ancient World and how, even the Ancient Egyptians were able to source rare spices from half a world away.

Please not that this recipe page (and all the other recipe pages on this site) are brought to you in association with the 'One Million People' campaign, which attempts to make available a number of ancient texts (particularly those relating to recipes) available for free on this site.

This page is presented as part of my 'History of the Spice Trade' section of the FabulousFusionFood Recipes site. You can use the table below to navigate the various sections of this history:

Before it's possible to begin a history of the spice trade we need to define what precisely is meant by a spice. In terms of a modern definition, a spice obtained from the dried fruiting body of a plant. Thus it can be the whole fruit (as in cubeb pepper or allspice berries or cumin) or it is the kernel or seed of the fruit (as in nutmeg and fenugreek seeds or nigella seeds). In contrast, herbs are the vegetative parts of a plant (the stems and leaves) and include lemongrass (stems), thyme (leaves), oregano (leaves). One exception to this rule is the Methi curry leaves (which are the dried leaves of fenugreek) which is generally considered as a spice.

In addition the roots and bark of plants in their dried form are also considered as spices. Thus turmeric and wasabi are spices (both derived from roots), as is cinnamon (a bark). (If you would like to learn more about spices, then please browse this site's Guide to Spices.

In ancient times a spice seems to have been defined mare as anything that bore a strong aroma. Thus herbs, spices and incense could all come under the label 'spice'. Perhaps the most important aspect of an ancient 'spice' was that it should not be perishable and could be transported for many months with little loss of pungency.

The Spice Trade

Humans have probably employed spices since we first began to cook with fire. After all, spices are just the seeds of naturally-occurring trees and plants. In Europe we know of juniper berries and mustard seeds from neolithic burials. However, most of the best-known spices derive either from the East (India and South-east Asia) or from the New World (Mexico and the Caribbean). Many of these spices (think of pepper and chillies) have become so ubiquitous that it's difficult to reconcile the fact that until very recently they were rare and expensive commodities.

Indeed, the history of commerce and trade is the history of spices and it's no exaggeration to say that America would not have been discovered were it not for the European desire to break the Arab traders' monopoly on spices. But to understand the spice trade we need to go back to its origins, which can actually be traced back five thousand years in the historical records (and probably represents a trade that's thousands of years older than that).

Origins of the Spice Trade

The first written record of spices being used comes from the Assyrians (circa 3000 BCE). What is recorded is a myth that claims that the gods drank sesame wine on the night before they created the earth. Use of sesame as a flavouring is so ancient and widespread that it is difficult now to know the true origin of this spice. Though recent genetic evidence suggests that the plant originated near the Indian subcontinent. Thus the Assyrian myth represents our first historical evidence for an ancient spice trade.

Further evidence is provided by Egyptian records where, as far back as 2600 BCE, the labourers building Cheops' great pyramid were fed Asiatic spices to give them strength. Archaeological evidence from Sumeria (circa 2400 BCE) also suggests that cloves were popular in Syria (cloves could only be attained from the Indonesian Spice Islands, the Moluccas). Strong evidence that trade with the spice islands themselves is truly ancient.

Almost a millennium later, the remarkable Egyptian Ebers papyrus (dating to 1550 BCE) lists spices used for both medicinal and embalming procedures. Cassia and cinnamon, named in the papyrus, were essential for embalming; as were anise, marjoram and cumin — all used to rinse-out the body cavities of the worthy dead. Of these spices, cassia and cinnamon are both native to south-east Asia.

Hammurabi (1792–1750 BCE) in his legal codes introduced severe penalties for sloppy or unsuccessful surgeons. This led to the use of medicinal spices in Sumaria and engendered a major spice trade there.

Egyptian records reveal that one of the female pharaoh Hatshepsut's (1473–1458 BCE) most famous exploits was her expedition to Punt (modern Somalia) where aromatic herbs and spices were gained and brought back to Egypt. Examination of the mummy of her descendant, Rameses II (died 1213 BCE) revealed that he had peppercorns inserted into each nostril.

All these separate pieces of evidence point towards the ancientness of the trade between the Middle East and India, China, South-east Asia and the Spice Islands of Indonesia. We also gain an indication of the economic importance of spices. Certainly they were worth legalizing, saving for royal burials and mounting large and expensive expeditions to go in search of them.

During these ancient times spices were probably traded from local merchant to local merchant and made their way slowly from east to west (with the volume of each spice decreasing and its economic importance increasing with each trade).

Start of the Arabic Spice Trade

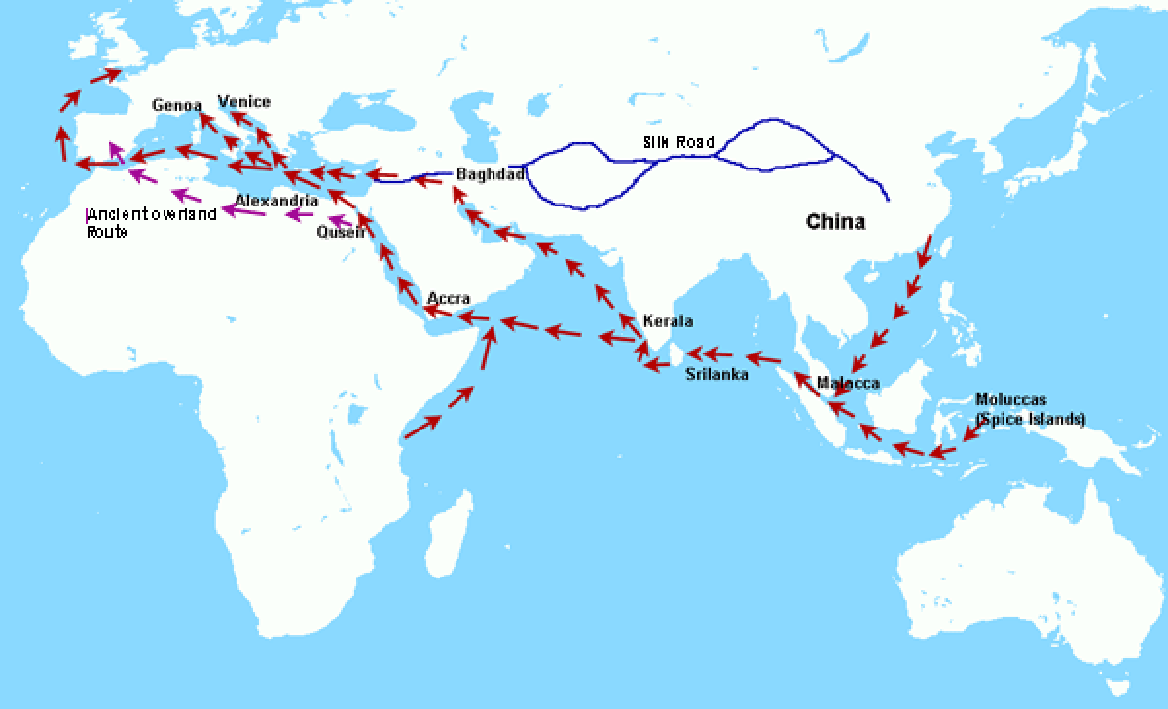

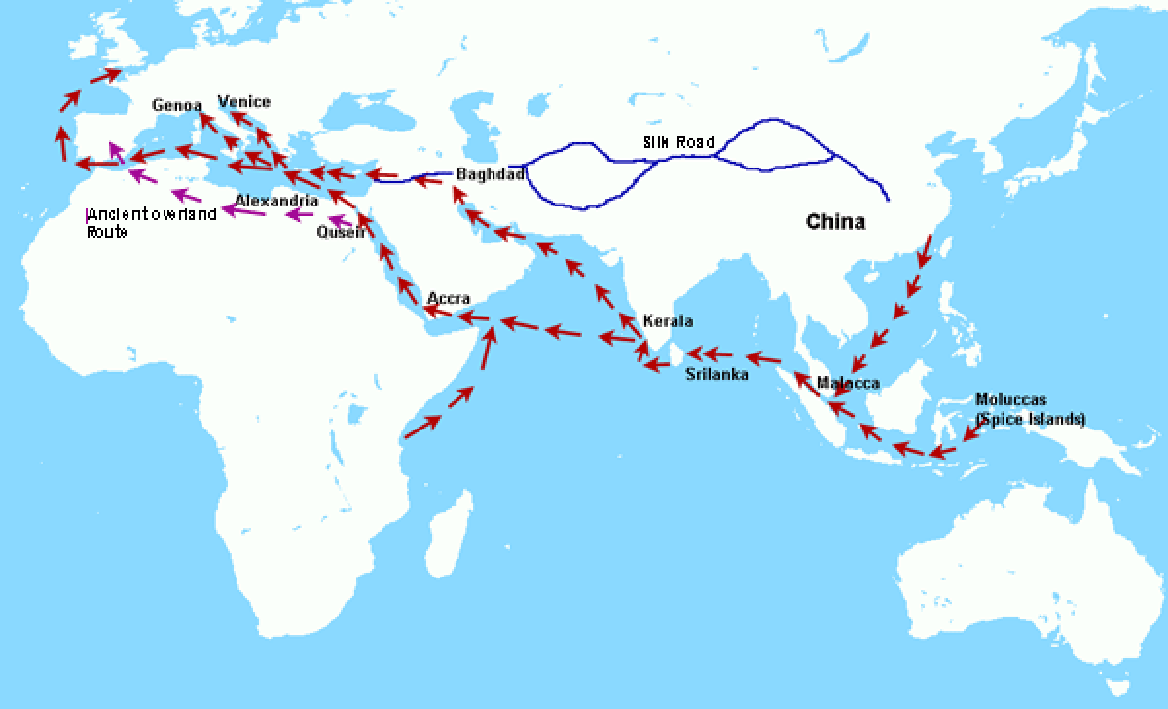

Fig 1: Map showing the ancient spice route from China to the spice islands of Indonesia and from Arabia to India and then to the Spice Islands. As well as the Mediterranean routes to Europe the old route across North Africa is shown. Also included on the map (blue lines) is the silk road extending from the Middle East to China.

Fig 1: Map showing the ancient spice route from China to the spice islands of Indonesia and from Arabia to India and then to the Spice Islands. As well as the Mediterranean routes to Europe the old route across North Africa is shown. Also included on the map (blue lines) is the silk road extending from the Middle East to China.

By about 950 BCE Nabataean (northern Arabic) traders began caravanning through India and China using strings of camels and donkeys. They established the first of the great caravan routes — the Incense Route. However, unlike the great Silk Road from Arabia to China the Incense Route was not fixed and by 24 BCE it had largely become a sea trading route (the Spice Route). Much of the focus of the early Incense Route was on gaining incense and spices that could then be sold to the Greeks (and which could bypass the Persians, the Greeks' implacable enemies).

By about 950 BCE Nabataean (northern Arabic) traders began caravanning through India and China using strings of camels and donkeys. They established the first of the great caravan routes — the Incense Route. However, unlike the great Silk Road from Arabia to China the Incense Route was not fixed and by 24 BCE it had largely become a sea trading route (the Spice Route). Much of the focus of the early Incense Route was on gaining incense and spices that could then be sold to the Greeks (and which could bypass the Persians, the Greeks' implacable enemies).

As the spice trade moved more into a maritime rather than an overland trade the Southern Arabic traders became more involved in the trade. In some respects the domination of the spice trade by both the Nabataeans and the Southern Arabians is a direct consequence of the Arabian Peninsula's location at the crossroads of Europe, Africa and Asia. Factor into this the ancient over-land trade links between the Arab traders and the lands of India and China and it is hardly surprising that a Spice Route evolved to link Arabia with Baghdad, India, Guangzhou in China and the straits of Molucca (the Spice Islands).

Certainly by the fifth century BCE the Arabic peoples had cornered the entire spice marked with the Mediterranean. To protect their very lucrative trade they created very elaborate tales as regards the origins of the spices they traded, as related by the Greek author, Herodotus (484–425 BCE). One of the most famous tales related by Herodotus tells of how cinnamon was obtained:

These tales were originally taken at face value, after all spices were known to be difficult and challenging to attain. Originating, as they did, in lands beyond the ken of man. But by the first century BCE Theophratus, whilst repeating the above tale, mentions known trade between Arabia and India in 'other spices'. By the time of the writing of his 'Natural Histories' (circa 30 CE) Pliny the Elder entirely discounts the tale (though he wrongly attributes the source of cassis as Ethiopia).

Certainly, by the second century BCE (as attested by both linguistic and archaeological evidence) the inhabitants of the Moluccas were trading in a circuit that extended from China in the east as far as India and even Arabia in the west. By the first century BCE the Arab traders were making direct voyages to India and the Chinese were making voyages throughout the entirety of the Malay archipelago to trade in the Moluccas. In effect the Spice Route had become an almost entirely maritime trading route.

Much of the trade was centred around Kerala in India (the heartlands of pepper production). From there the route either went northwards via the western Arabian peninsula before taking the over-land route to Baghdad (figure 1) where it joined with the Silk Road. Alternatively trade went southwards towards the western Arabian peninsula and the coast of Egypt. Recent excavations indicate that Quaseir-al-Quadim (ancient Myos Hormos, just north-east of Luxor) was a very important port in the spice trade as a whole. From there the spices either moved over-land to Libya, Spain and Europe or traversed the Mediterranean — first to destinations in Greece and then to Rome.

So lucrative was the spice trade that after his conquest of Egypt in 332–331 BCE Alexander the Great founded Alexandria as a port for the extension of the spice trade into the Mediterranean. Even though the Arab traders still effectively controlled the spice trade Alexandria grew wealthy simply on the duties levied on these exports — a fact that provides us with a good indication of how lucrative this trade actually was.

The Roman Age

As Alexandria was steadily growing wealthy on the back of the spice trade a new power was slowly raising to prominence in the Mediterranean. What had once been the rather backwards city state of Rome had grown into a giant naval and military power — so much so that by the mid second century BCE they referred to the Mediterranean sea as Mare Nostrum (Our Sea).

As Alexandria was steadily growing wealthy on the back of the spice trade a new power was slowly raising to prominence in the Mediterranean. What had once been the rather backwards city state of Rome had grown into a giant naval and military power — so much so that by the mid second century BCE they referred to the Mediterranean sea as Mare Nostrum (Our Sea).

After the razing of Corinth in 146 BCE and the suppression of democracy in Greece the Greeks effectively became client peoples of Rome. This led to the adoption of Greek cooking methods by the Romans as more and more Greek cooks were brought as slaves to Rome. As a result Romans became huge consumers of spices.

In 80 BCE Ptolemy XI bequeathed Alexandria to the Romans and under their leadership Alexandria became the world's greatest centre of commerce and the primary marketplace for the Arab-controlled spice trade. Much of this trade was with the Nabataeans — who were allies of Rome. Yet, during the first century CE the Roman demand for spices was causing concern for many notable Romans (amongst them Pliny the Elder) who rued the way that the Empire's gold seemed to flow steadily to the East. Pliny's aim was to expose the truth of the spice trade (rather than the fanciful legends proffered by Arab merchants).

From an historical perspective this seems rather odd, as we know that during the reign of Ptolemy VII (circa 116 BCE) a Greek sailor did manage to sail with the trade winds to reach Kerala in India. This led to a nascent Egyptian spice trade (though it was dwarfed by the Arabian trade) where the Egyptian Greeks were careful to avoid long voyages close to the Arab-controlled shoreline of India. Despite the Romans having taken-over Alexandria it does seem that knowledge of this trade route was effectively lost.

Resentment of he Arab stranglehold on the spice trade eventually led Rome — as was their want — to launch an invasion of Arabia in 24 BCE. This invasion, however, led to complete humiliation for the Roman legions. However, the defeat only made the Romans more determined to break the Arab monopoly. Intelligence on the spice trade was slowly gathered and in 40CE Hippalus, a Greek merchant, discovered the secret of the East Indian trade winds — a secret that the Arab traders had managed to keep hidden for almost a millennium. It turns out that the monsoons which act to nourish India's pepper vines actually reverse direction mid-year. Thus trips from the Red Sea coast of Egypt to India and back could be made far shorter and in greater safety than the Romans had ever imagined. Direct Roman trade with India blossomed and the Arab monopoly was broken.

To us — who use pepper almost ubiquitously in our cooking — it is almost impossible to imagine how wonderful and miraculous this once-rare spice was in the past. For it modified the flavour of food and had the ability to preserve pickles and to mask the taste of tainted meat (crucial before refrigeration). Romans were the first major users of pepper and dishes employing pepper are described in Roman writings as early as the first century CE. By the fourth century over 85% of the recipes in Apicius' cook-book De Re Coquinaria (many of which are translated and updated here used pepper as an ingredient.

In many ways, pepper was a valuable resource. So much so that salaries and tributes could be paid in pepper. Indeed, during the twilight of the Roman Empire when Alaric the Visigoth captured Rome in 440 CE he demanded 3000 peppercorns as part of the price for sparing Rome's inhabitants.

By the fourth century CE, however, the Roman trade with India began to weaken and decline, allowing Arab and Ethiopian merchants to re-gain control of the trade. With the move of the heart of the Roman empire to Constantinople the Roman spice trade revived during the fifth century CE but even this trade had dwindled almost to nothing by the sixth century.

The sixth century CE seems to represent a time of no real dominance over the spice trade — with Arabic, Ethiopian, Gudjrati and even Radhamite Jewish merchants plying the spice routes.

This had a dramatic effect on Europe and led, ultimately to Europe's 'Age of Discovery' and the finding of the New World as well as the discovery of the location of the New World. You can read about this period in the history of the spice trade in the next section of this article: The Dark Ages and the Age of Discovery.

For classic examples of Roman cookery and how spices are used in traditional Roman dishes, this site has the full text of Apicius' De Re Coquinaria (On Cooking) a classic Roman cookbook, with English translation and modern redactions of many of the recipes.

Please not that this recipe page (and all the other recipe pages on this site) are brought to you in association with the 'One Million People' campaign, which attempts to make available a number of ancient texts (particularly those relating to recipes) available for free on this site.

This page is presented as part of my 'History of the Spice Trade' section of the FabulousFusionFood Recipes site. You can use the table below to navigate the various sections of this history:

History Of the Spice Trade — The Ancient World

What is a Spice?What is a Spice?

Before it's possible to begin a history of the spice trade we need to define what precisely is meant by a spice. In terms of a modern definition, a spice obtained from the dried fruiting body of a plant. Thus it can be the whole fruit (as in cubeb pepper or allspice berries or cumin) or it is the kernel or seed of the fruit (as in nutmeg and fenugreek seeds or nigella seeds). In contrast, herbs are the vegetative parts of a plant (the stems and leaves) and include lemongrass (stems), thyme (leaves), oregano (leaves). One exception to this rule is the Methi curry leaves (which are the dried leaves of fenugreek) which is generally considered as a spice.

In addition the roots and bark of plants in their dried form are also considered as spices. Thus turmeric and wasabi are spices (both derived from roots), as is cinnamon (a bark). (If you would like to learn more about spices, then please browse this site's Guide to Spices.

In ancient times a spice seems to have been defined mare as anything that bore a strong aroma. Thus herbs, spices and incense could all come under the label 'spice'. Perhaps the most important aspect of an ancient 'spice' was that it should not be perishable and could be transported for many months with little loss of pungency.

The Spice Trade

Humans have probably employed spices since we first began to cook with fire. After all, spices are just the seeds of naturally-occurring trees and plants. In Europe we know of juniper berries and mustard seeds from neolithic burials. However, most of the best-known spices derive either from the East (India and South-east Asia) or from the New World (Mexico and the Caribbean). Many of these spices (think of pepper and chillies) have become so ubiquitous that it's difficult to reconcile the fact that until very recently they were rare and expensive commodities.

Indeed, the history of commerce and trade is the history of spices and it's no exaggeration to say that America would not have been discovered were it not for the European desire to break the Arab traders' monopoly on spices. But to understand the spice trade we need to go back to its origins, which can actually be traced back five thousand years in the historical records (and probably represents a trade that's thousands of years older than that).

Origins of the Spice Trade

The first written record of spices being used comes from the Assyrians (circa 3000 BCE). What is recorded is a myth that claims that the gods drank sesame wine on the night before they created the earth. Use of sesame as a flavouring is so ancient and widespread that it is difficult now to know the true origin of this spice. Though recent genetic evidence suggests that the plant originated near the Indian subcontinent. Thus the Assyrian myth represents our first historical evidence for an ancient spice trade.

Further evidence is provided by Egyptian records where, as far back as 2600 BCE, the labourers building Cheops' great pyramid were fed Asiatic spices to give them strength. Archaeological evidence from Sumeria (circa 2400 BCE) also suggests that cloves were popular in Syria (cloves could only be attained from the Indonesian Spice Islands, the Moluccas). Strong evidence that trade with the spice islands themselves is truly ancient.

Almost a millennium later, the remarkable Egyptian Ebers papyrus (dating to 1550 BCE) lists spices used for both medicinal and embalming procedures. Cassia and cinnamon, named in the papyrus, were essential for embalming; as were anise, marjoram and cumin — all used to rinse-out the body cavities of the worthy dead. Of these spices, cassia and cinnamon are both native to south-east Asia.

Hammurabi (1792–1750 BCE) in his legal codes introduced severe penalties for sloppy or unsuccessful surgeons. This led to the use of medicinal spices in Sumaria and engendered a major spice trade there.

Egyptian records reveal that one of the female pharaoh Hatshepsut's (1473–1458 BCE) most famous exploits was her expedition to Punt (modern Somalia) where aromatic herbs and spices were gained and brought back to Egypt. Examination of the mummy of her descendant, Rameses II (died 1213 BCE) revealed that he had peppercorns inserted into each nostril.

All these separate pieces of evidence point towards the ancientness of the trade between the Middle East and India, China, South-east Asia and the Spice Islands of Indonesia. We also gain an indication of the economic importance of spices. Certainly they were worth legalizing, saving for royal burials and mounting large and expensive expeditions to go in search of them.

During these ancient times spices were probably traded from local merchant to local merchant and made their way slowly from east to west (with the volume of each spice decreasing and its economic importance increasing with each trade).

Start of the Arabic Spice Trade

Fig 1: Map showing the ancient spice route from China to the spice islands of Indonesia and from Arabia to India and then to the Spice Islands. As well as the Mediterranean routes to Europe the old route across North Africa is shown. Also included on the map (blue lines) is the silk road extending from the Middle East to China.

Fig 1: Map showing the ancient spice route from China to the spice islands of Indonesia and from Arabia to India and then to the Spice Islands. As well as the Mediterranean routes to Europe the old route across North Africa is shown. Also included on the map (blue lines) is the silk road extending from the Middle East to China.

By about 950 BCE Nabataean (northern Arabic) traders began caravanning through India and China using strings of camels and donkeys. They established the first of the great caravan routes — the Incense Route. However, unlike the great Silk Road from Arabia to China the Incense Route was not fixed and by 24 BCE it had largely become a sea trading route (the Spice Route). Much of the focus of the early Incense Route was on gaining incense and spices that could then be sold to the Greeks (and which could bypass the Persians, the Greeks' implacable enemies).

By about 950 BCE Nabataean (northern Arabic) traders began caravanning through India and China using strings of camels and donkeys. They established the first of the great caravan routes — the Incense Route. However, unlike the great Silk Road from Arabia to China the Incense Route was not fixed and by 24 BCE it had largely become a sea trading route (the Spice Route). Much of the focus of the early Incense Route was on gaining incense and spices that could then be sold to the Greeks (and which could bypass the Persians, the Greeks' implacable enemies).

As the spice trade moved more into a maritime rather than an overland trade the Southern Arabic traders became more involved in the trade. In some respects the domination of the spice trade by both the Nabataeans and the Southern Arabians is a direct consequence of the Arabian Peninsula's location at the crossroads of Europe, Africa and Asia. Factor into this the ancient over-land trade links between the Arab traders and the lands of India and China and it is hardly surprising that a Spice Route evolved to link Arabia with Baghdad, India, Guangzhou in China and the straits of Molucca (the Spice Islands).

Certainly by the fifth century BCE the Arabic peoples had cornered the entire spice marked with the Mediterranean. To protect their very lucrative trade they created very elaborate tales as regards the origins of the spices they traded, as related by the Greek author, Herodotus (484–425 BCE). One of the most famous tales related by Herodotus tells of how cinnamon was obtained:

Their manner of collecting the cassia is the following: They cover all their body and their face with the hides of oxen and other skins, leaving only holes for the eyes, and thus protected go in search of the cassia, which grows in a lake of no great depth. All round the shores and in the lake itself there dwell a number of winged animals much resembling bats, which screech horribly, and are very valiant. These creatures they must keep from their eyes all the while that they gather the cassia. Still more wonderful is the mode in which they collect the cinnamon. Where the wood grows, and what country produces it, they cannot tell only some, following probability, relate that it comes from the country in which Bacchus was brought up. Great birds, they say, bring the sticks which we Greeks, taking the word from the Phoenicians, call cinnamon, and carry them up into the air to make their nests. These are fastened with a sort of mud to a sheer face of rock, where no foot of man is able to climb. So the Arabians, to get the cinnamon, use the following artifice. They cut all the oxen and asses and beasts of burden that die in their land into large pieces, which they carry with them into those regions, and place near the nests: then they withdraw to a distance, and the old birds, swooping down, seize the pieces of meat and fly with them up to their nests; which not being able to support the weight, break off and fall to the ground. Whereupon the Arabians return and collect the cinnamon which is afterwards carried from Arabia into other countries.

These tales were originally taken at face value, after all spices were known to be difficult and challenging to attain. Originating, as they did, in lands beyond the ken of man. But by the first century BCE Theophratus, whilst repeating the above tale, mentions known trade between Arabia and India in 'other spices'. By the time of the writing of his 'Natural Histories' (circa 30 CE) Pliny the Elder entirely discounts the tale (though he wrongly attributes the source of cassis as Ethiopia).

Certainly, by the second century BCE (as attested by both linguistic and archaeological evidence) the inhabitants of the Moluccas were trading in a circuit that extended from China in the east as far as India and even Arabia in the west. By the first century BCE the Arab traders were making direct voyages to India and the Chinese were making voyages throughout the entirety of the Malay archipelago to trade in the Moluccas. In effect the Spice Route had become an almost entirely maritime trading route.

Much of the trade was centred around Kerala in India (the heartlands of pepper production). From there the route either went northwards via the western Arabian peninsula before taking the over-land route to Baghdad (figure 1) where it joined with the Silk Road. Alternatively trade went southwards towards the western Arabian peninsula and the coast of Egypt. Recent excavations indicate that Quaseir-al-Quadim (ancient Myos Hormos, just north-east of Luxor) was a very important port in the spice trade as a whole. From there the spices either moved over-land to Libya, Spain and Europe or traversed the Mediterranean — first to destinations in Greece and then to Rome.

So lucrative was the spice trade that after his conquest of Egypt in 332–331 BCE Alexander the Great founded Alexandria as a port for the extension of the spice trade into the Mediterranean. Even though the Arab traders still effectively controlled the spice trade Alexandria grew wealthy simply on the duties levied on these exports — a fact that provides us with a good indication of how lucrative this trade actually was.

The Roman Age

As Alexandria was steadily growing wealthy on the back of the spice trade a new power was slowly raising to prominence in the Mediterranean. What had once been the rather backwards city state of Rome had grown into a giant naval and military power — so much so that by the mid second century BCE they referred to the Mediterranean sea as Mare Nostrum (Our Sea).

As Alexandria was steadily growing wealthy on the back of the spice trade a new power was slowly raising to prominence in the Mediterranean. What had once been the rather backwards city state of Rome had grown into a giant naval and military power — so much so that by the mid second century BCE they referred to the Mediterranean sea as Mare Nostrum (Our Sea).

After the razing of Corinth in 146 BCE and the suppression of democracy in Greece the Greeks effectively became client peoples of Rome. This led to the adoption of Greek cooking methods by the Romans as more and more Greek cooks were brought as slaves to Rome. As a result Romans became huge consumers of spices.

In 80 BCE Ptolemy XI bequeathed Alexandria to the Romans and under their leadership Alexandria became the world's greatest centre of commerce and the primary marketplace for the Arab-controlled spice trade. Much of this trade was with the Nabataeans — who were allies of Rome. Yet, during the first century CE the Roman demand for spices was causing concern for many notable Romans (amongst them Pliny the Elder) who rued the way that the Empire's gold seemed to flow steadily to the East. Pliny's aim was to expose the truth of the spice trade (rather than the fanciful legends proffered by Arab merchants).

From an historical perspective this seems rather odd, as we know that during the reign of Ptolemy VII (circa 116 BCE) a Greek sailor did manage to sail with the trade winds to reach Kerala in India. This led to a nascent Egyptian spice trade (though it was dwarfed by the Arabian trade) where the Egyptian Greeks were careful to avoid long voyages close to the Arab-controlled shoreline of India. Despite the Romans having taken-over Alexandria it does seem that knowledge of this trade route was effectively lost.

Resentment of he Arab stranglehold on the spice trade eventually led Rome — as was their want — to launch an invasion of Arabia in 24 BCE. This invasion, however, led to complete humiliation for the Roman legions. However, the defeat only made the Romans more determined to break the Arab monopoly. Intelligence on the spice trade was slowly gathered and in 40CE Hippalus, a Greek merchant, discovered the secret of the East Indian trade winds — a secret that the Arab traders had managed to keep hidden for almost a millennium. It turns out that the monsoons which act to nourish India's pepper vines actually reverse direction mid-year. Thus trips from the Red Sea coast of Egypt to India and back could be made far shorter and in greater safety than the Romans had ever imagined. Direct Roman trade with India blossomed and the Arab monopoly was broken.

To us — who use pepper almost ubiquitously in our cooking — it is almost impossible to imagine how wonderful and miraculous this once-rare spice was in the past. For it modified the flavour of food and had the ability to preserve pickles and to mask the taste of tainted meat (crucial before refrigeration). Romans were the first major users of pepper and dishes employing pepper are described in Roman writings as early as the first century CE. By the fourth century over 85% of the recipes in Apicius' cook-book De Re Coquinaria (many of which are translated and updated here used pepper as an ingredient.

In many ways, pepper was a valuable resource. So much so that salaries and tributes could be paid in pepper. Indeed, during the twilight of the Roman Empire when Alaric the Visigoth captured Rome in 440 CE he demanded 3000 peppercorns as part of the price for sparing Rome's inhabitants.

By the fourth century CE, however, the Roman trade with India began to weaken and decline, allowing Arab and Ethiopian merchants to re-gain control of the trade. With the move of the heart of the Roman empire to Constantinople the Roman spice trade revived during the fifth century CE but even this trade had dwindled almost to nothing by the sixth century.

The sixth century CE seems to represent a time of no real dominance over the spice trade — with Arabic, Ethiopian, Gudjrati and even Radhamite Jewish merchants plying the spice routes.

This had a dramatic effect on Europe and led, ultimately to Europe's 'Age of Discovery' and the finding of the New World as well as the discovery of the location of the New World. You can read about this period in the history of the spice trade in the next section of this article: The Dark Ages and the Age of Discovery.

For classic examples of Roman cookery and how spices are used in traditional Roman dishes, this site has the full text of Apicius' De Re Coquinaria (On Cooking) a classic Roman cookbook, with English translation and modern redactions of many of the recipes.