A mixture of spices shown in bowls that feature in this guide.

A mixture of spices shown in bowls that feature in this guide.

Welcome to the Celtnet Recipes page for the History of the Spice Trade. This is the second page, in a series of articles, gives you an introduction to the spice trade during the Middle Ages.

Please not that this recipe page (and all the other recipe pages on this site) are brought to you in association with the 'One Million People' campaign, which attempts to make available a number of ancient texts (particularly those relating to recipes) available for free on this site.

This page is presented as part of my 'History of the Spice Trade' section of the FabulousFusionFood Recipes site. You can use the table below to navigate the various sections of this history:

The Muslim Age

As we shall see, the early history of Islam and the resurgence of the Arabic hold on the spice trade are inexorable intertwined. To understand why we have to go back to the very beginnings of the Muslim faith.

As we shall see, the early history of Islam and the resurgence of the Arabic hold on the spice trade are inexorable intertwined. To understand why we have to go back to the very beginnings of the Muslim faith.

Indeed, Muhammad's first wife, Khadijeh was the widow of a spice trader and her wealth and prestiege were a driving force behind Muhammad himself. In 622 CE (1 AH [after Hajira in the Muslem calendar]), Muhammad made his journey from the 'pagan and wicked community' of Mekka to Yathrib (modern Medina) where the peoples 'lived in accordance with the moral teachings of Islam'. Muhammad's path on this journey was prepared by the local traders who eased his way.

At Yathrib Muhammad obtained more converts and began building a powerful base for himself. This brought him into conflict with his Qurashi neighbours, quite probably as a result of a dominance struggle for the trade routes south. Desire for mastery of these trade routes brought the most significant expansion of the religion of Islam and saw its return to its homeland of Mekka.

In effect Muhammad engendereda far more aggressive and expanionist form of Islam that still respected his own interest in the spice trade. Indeed, the spice routes became one of the main ways that early Islam was exported to other lands. As Islam can only be expressed in classical Arabic this meant the export of Arabic culture and language as well as belief.

Over the next three centuries the nature of Islam solidified and crystallized so that by the tenth century CE the Qu'ran had been written and was widely distributed, the hadith had been codifeied (this is a collection of the sayings and deeds of Muhammad). The rights of Muslims and non-Muslims in a Muslim world had also been codified and though Jews and Christians had some protection as 'peoples of the book' they were still second-class citizens and if you were a true infidel then you had no protection under Muslim law. This distinction between Muslim and non-Muslim invariably led to the view of a dichotomous world where the Muslims lived in Dar al-Islam (the House of Islam [or Submission]) and everyone else dwelt in the Dar al-Harb (the House of War).

Just as Islam was fortifying itself and consolidating its identity and steps were being taken to convert more followers Arabs were also becoming more and more involved in trading. Obviously Arabs had been involved in the spice trade for millennia already, but the conversion of the Arab world to the Muslim faith brought with it a characteristic Muslim attitude to improving the spice trade. Prior to Muslim conquest most trade was indirect and created by overlapping networks of local merchants who traded exclusively in their own domains. To make the spice trade exclusively Muslim the main staging posts along the spice route were conquered my Muslim forces. This way Muslims could travel the entire length of the trade routes themselves and did not have to rely on intermediaries. This also markedly increased their ability to spread the word of both Allah and Muhammad. By the end of the tenth century the entire spice route had been converted into a Muslim spice route under the exclusive control of Arab traders.

In taking Alexandria in 641 CE and in stopping all communication with Europe by the mid eighth century the Muslim world brought down what's been termed the 'Islamic Curtain' between Europe and Asia and effectively ended the westward flow of spices with considerable consequences for Europe.

European Dark Ages

This represents the period from about 641–1096 CE, the time of the 'Islamic Curtain' where all trade between Christian Europe and the Muslim East was curtailed. The westward flow of spices almost dried-up completely with only a few Jewish traders (who could dwell in both the Christian and Muslim worlds) bringing-in tiny amounts of very expensive spices. So expensive did these become that they could only be afforded by the very wealthy (we know that the Frankish Merovingian and Carolingian dynasties were able to source cinnamon, nutmeg, cloves and pepper). By the tenth century, however, the rise of the great city states of Venice and Genoa proved an almost irresistible source of wealth to Arab traders and spices began to trickle into Europe via these ports.

We know little of European diets from these times. There are no recipe books and what little information comes to us originates only from the largest courts. The reality is that spices would have been extremely expensive and by-and-large Feudal Europe was to poor to afford luxuries such as spices.

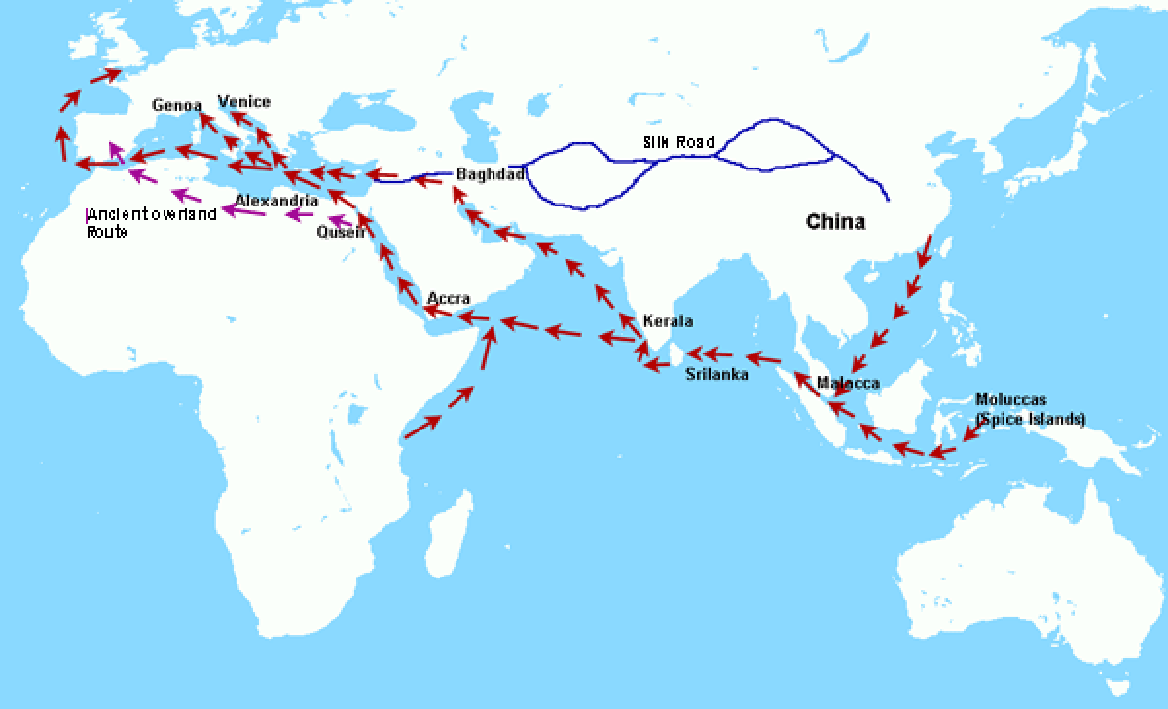

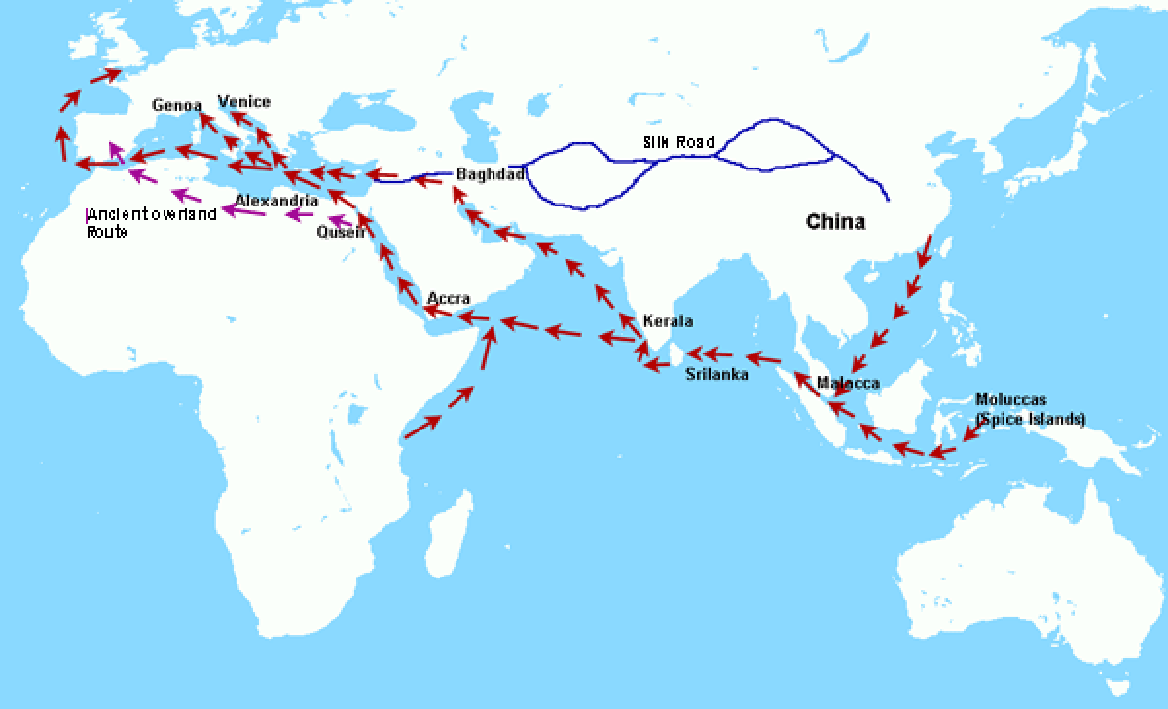

Fig 1: Map showing the ancient spice route from China to the spice islands of Indonesia and from Arabia to India and then to the Spice Islands. As well as the Mediterranean routes to Europe the old route across North Africa is shown. Also included on the map (blue lines) is the silk road extending from the Middle East to China.

Fig 1: Map showing the ancient spice route from China to the spice islands of Indonesia and from Arabia to India and then to the Spice Islands. As well as the Mediterranean routes to Europe the old route across North Africa is shown. Also included on the map (blue lines) is the silk road extending from the Middle East to China.

The Crusades and After

This period in European history covers 1097 to 1490 CE. It represents what is probably the most successful period in the Catholic Church's history, culminating in the Christianization of all of Northern Europe. This led to a large number of warrior peoples (such as the Vikings, Slavs and Magyars) being brought into the Christian fold. Christendom now had thousands of warriors within its borders with little to do. Many of these warriors were employed in the Reconquista in Spain and this is where the idea of a holy war to regain Christendom emerged. After the Byzantine emperor Alexius I called for help with defending his empire against the Seljuk Turks, in 1095 at the Council of Clermont Pope Urban II called upon all Christians to join a war against the Turks, a war which would count as full penance. Crusader armies marched to Jerusalem, sacking several cities on their way. In 1099, they took Jerusalem and massacred the population. The returning crusader knights brought with them treasure chests from the East. Chests filled not with treasures of gold and silver but rather peppercorns and rare spices.

This period in European history covers 1097 to 1490 CE. It represents what is probably the most successful period in the Catholic Church's history, culminating in the Christianization of all of Northern Europe. This led to a large number of warrior peoples (such as the Vikings, Slavs and Magyars) being brought into the Christian fold. Christendom now had thousands of warriors within its borders with little to do. Many of these warriors were employed in the Reconquista in Spain and this is where the idea of a holy war to regain Christendom emerged. After the Byzantine emperor Alexius I called for help with defending his empire against the Seljuk Turks, in 1095 at the Council of Clermont Pope Urban II called upon all Christians to join a war against the Turks, a war which would count as full penance. Crusader armies marched to Jerusalem, sacking several cities on their way. In 1099, they took Jerusalem and massacred the population. The returning crusader knights brought with them treasure chests from the East. Chests filled not with treasures of gold and silver but rather peppercorns and rare spices.

These rare spices were brought back to Northern Europe and they began to be used in regular cookery. Both the tastes and the modes of living of the East created a lasting impression on the Crusader knights and they had a profound effect on the cuisine and habits of Europe. Oddly enough trade with the East opened up and the ports of Genoa and Venice in the south and Antwerp and Bruges began to supply the increasing demand for spices. It is interesting in fact, when looking at recipes from recipes from this period in the Medieval age just how highly spiced some of the dishes are. However, Venice's almost exclusive deal with the Arab traders meant that by the thirteenth century almost the entire profits from the European spice trade went to Venice. Yet the Venetian traders wanted a greater slice of the spice pie for themselves and in about 1271 Marco Polo set out overland from Venice across the Crimea in search of the fabled gems and spices of the far east.

Once again spices became an essential part of everyday European life. So much so that 1180 a Pepperers' guild had been established in London that was rapidly transformed into a Spicers' guild. The members of these guilds were in effect the forerunners of apothecaries and spices beceame one of the most important ingredients in the medical practice of the age. This period in history also corresponds with the great Mongol expansion, beginning with the conquests of Genghis Khan (1162–1227). The Mongolian Khans effectively controlled the entirety of the Silk Road and trade with Europe redoubled. Many merchant families (especially from Venice) funded their own caravans to the east and became wealthy on the proceeds. Such a family were the Polos of Venice and in 1271 who travelled with his father Niccòlo and uncle Maffeo (who had previously journeyed to Cathay [China]) with the Pope's response to Kubulai Khan's request for educated people to come and teach Christianity and Western customs to his people. They travelled to Kubulai Khan's court where Marco became a favourite of the Khan and was employed for 17 years. In 1291 Kublai entrusted Marco with his final duty, to escort the Mongol princess Koekecin to her betrothed, the Ilkhan Arghun. They reached the Ilkhanate in 1293 and from there moved to Trabzon where they set sail for Venice. On their return from China in 1295, the family settled in Venice where they became a sensation and attracted crowds of listeners who had difficulties in believing their reports of distant China. Marco Polo was later captured in a minor clash of the war between Venice and Genoa, He spent the few months of his imprisonment, in 1298, dictating to a fellow prisoner, Rustichello da Pisa, a detailed account of his travels in the then-unknown parts of the Far East. This journey became on of the most celebrated early travelogues and became one of the inspirations for the later 'Age of Discovery'.

As well as bringing spices to Europe it is also quite possible that the Spice route brought with it the Black Death that first struck Europe in 1347–1351 CE. Indeed, the disease first seems to have struck China in the mid 1330s and spread along the overland trade routes, first to the Middle East and then Europe. The high mortality of the Black Death caused major social upheaval in the lands which it struck. This led to pressure on the overland trade routes as the Khanate of the Mongols collapsed and various factions vied for dominance across the Arab world. Raiding became rife and the overland routes to the East became unsafe. However, a small amount of spice still managed to find its way into Europe by way of Constantinople. But a resurgent Ottoman Empire was slowly closing-off all the trade routes and by 1453 with the fall of Constantinople the final overland route for spices into Europe was closed off. This effectively left Venice with a virtual monopoly on all spice reaching Europe by the sea routes. So confident were the Egyptians of the Venetian monopoly (they controlled the port of Alexandria from whence the spice reached Venice) that in 1453 they introduced a tariff on all the spices leaving Alexandria that amounted to a third of the total value of the spices.

Obviously, the situation for the remainder of Europe was untenable and the only solution was to find the sea route to the spice lands. This was the impetus for the period in European history that later became known as 'The Age of Discovery'.

The next section in this article deals with the European ages of Discovery and Conquest and how the quest for new sources of spices led to Europeans discovering and attempting to conquer the globe.

Please not that this recipe page (and all the other recipe pages on this site) are brought to you in association with the 'One Million People' campaign, which attempts to make available a number of ancient texts (particularly those relating to recipes) available for free on this site.

This page is presented as part of my 'History of the Spice Trade' section of the FabulousFusionFood Recipes site. You can use the table below to navigate the various sections of this history:

History Of the Spice Trade — The Middle Ages

The Muslim Age

As we shall see, the early history of Islam and the resurgence of the Arabic hold on the spice trade are inexorable intertwined. To understand why we have to go back to the very beginnings of the Muslim faith.

As we shall see, the early history of Islam and the resurgence of the Arabic hold on the spice trade are inexorable intertwined. To understand why we have to go back to the very beginnings of the Muslim faith.

Indeed, Muhammad's first wife, Khadijeh was the widow of a spice trader and her wealth and prestiege were a driving force behind Muhammad himself. In 622 CE (1 AH [after Hajira in the Muslem calendar]), Muhammad made his journey from the 'pagan and wicked community' of Mekka to Yathrib (modern Medina) where the peoples 'lived in accordance with the moral teachings of Islam'. Muhammad's path on this journey was prepared by the local traders who eased his way.

At Yathrib Muhammad obtained more converts and began building a powerful base for himself. This brought him into conflict with his Qurashi neighbours, quite probably as a result of a dominance struggle for the trade routes south. Desire for mastery of these trade routes brought the most significant expansion of the religion of Islam and saw its return to its homeland of Mekka.

In effect Muhammad engendereda far more aggressive and expanionist form of Islam that still respected his own interest in the spice trade. Indeed, the spice routes became one of the main ways that early Islam was exported to other lands. As Islam can only be expressed in classical Arabic this meant the export of Arabic culture and language as well as belief.

Over the next three centuries the nature of Islam solidified and crystallized so that by the tenth century CE the Qu'ran had been written and was widely distributed, the hadith had been codifeied (this is a collection of the sayings and deeds of Muhammad). The rights of Muslims and non-Muslims in a Muslim world had also been codified and though Jews and Christians had some protection as 'peoples of the book' they were still second-class citizens and if you were a true infidel then you had no protection under Muslim law. This distinction between Muslim and non-Muslim invariably led to the view of a dichotomous world where the Muslims lived in Dar al-Islam (the House of Islam [or Submission]) and everyone else dwelt in the Dar al-Harb (the House of War).

Just as Islam was fortifying itself and consolidating its identity and steps were being taken to convert more followers Arabs were also becoming more and more involved in trading. Obviously Arabs had been involved in the spice trade for millennia already, but the conversion of the Arab world to the Muslim faith brought with it a characteristic Muslim attitude to improving the spice trade. Prior to Muslim conquest most trade was indirect and created by overlapping networks of local merchants who traded exclusively in their own domains. To make the spice trade exclusively Muslim the main staging posts along the spice route were conquered my Muslim forces. This way Muslims could travel the entire length of the trade routes themselves and did not have to rely on intermediaries. This also markedly increased their ability to spread the word of both Allah and Muhammad. By the end of the tenth century the entire spice route had been converted into a Muslim spice route under the exclusive control of Arab traders.

In taking Alexandria in 641 CE and in stopping all communication with Europe by the mid eighth century the Muslim world brought down what's been termed the 'Islamic Curtain' between Europe and Asia and effectively ended the westward flow of spices with considerable consequences for Europe.

European Dark Ages

This represents the period from about 641–1096 CE, the time of the 'Islamic Curtain' where all trade between Christian Europe and the Muslim East was curtailed. The westward flow of spices almost dried-up completely with only a few Jewish traders (who could dwell in both the Christian and Muslim worlds) bringing-in tiny amounts of very expensive spices. So expensive did these become that they could only be afforded by the very wealthy (we know that the Frankish Merovingian and Carolingian dynasties were able to source cinnamon, nutmeg, cloves and pepper). By the tenth century, however, the rise of the great city states of Venice and Genoa proved an almost irresistible source of wealth to Arab traders and spices began to trickle into Europe via these ports.

We know little of European diets from these times. There are no recipe books and what little information comes to us originates only from the largest courts. The reality is that spices would have been extremely expensive and by-and-large Feudal Europe was to poor to afford luxuries such as spices.

Fig 1: Map showing the ancient spice route from China to the spice islands of Indonesia and from Arabia to India and then to the Spice Islands. As well as the Mediterranean routes to Europe the old route across North Africa is shown. Also included on the map (blue lines) is the silk road extending from the Middle East to China.

Fig 1: Map showing the ancient spice route from China to the spice islands of Indonesia and from Arabia to India and then to the Spice Islands. As well as the Mediterranean routes to Europe the old route across North Africa is shown. Also included on the map (blue lines) is the silk road extending from the Middle East to China.

The Crusades and After

This period in European history covers 1097 to 1490 CE. It represents what is probably the most successful period in the Catholic Church's history, culminating in the Christianization of all of Northern Europe. This led to a large number of warrior peoples (such as the Vikings, Slavs and Magyars) being brought into the Christian fold. Christendom now had thousands of warriors within its borders with little to do. Many of these warriors were employed in the Reconquista in Spain and this is where the idea of a holy war to regain Christendom emerged. After the Byzantine emperor Alexius I called for help with defending his empire against the Seljuk Turks, in 1095 at the Council of Clermont Pope Urban II called upon all Christians to join a war against the Turks, a war which would count as full penance. Crusader armies marched to Jerusalem, sacking several cities on their way. In 1099, they took Jerusalem and massacred the population. The returning crusader knights brought with them treasure chests from the East. Chests filled not with treasures of gold and silver but rather peppercorns and rare spices.

This period in European history covers 1097 to 1490 CE. It represents what is probably the most successful period in the Catholic Church's history, culminating in the Christianization of all of Northern Europe. This led to a large number of warrior peoples (such as the Vikings, Slavs and Magyars) being brought into the Christian fold. Christendom now had thousands of warriors within its borders with little to do. Many of these warriors were employed in the Reconquista in Spain and this is where the idea of a holy war to regain Christendom emerged. After the Byzantine emperor Alexius I called for help with defending his empire against the Seljuk Turks, in 1095 at the Council of Clermont Pope Urban II called upon all Christians to join a war against the Turks, a war which would count as full penance. Crusader armies marched to Jerusalem, sacking several cities on their way. In 1099, they took Jerusalem and massacred the population. The returning crusader knights brought with them treasure chests from the East. Chests filled not with treasures of gold and silver but rather peppercorns and rare spices.

These rare spices were brought back to Northern Europe and they began to be used in regular cookery. Both the tastes and the modes of living of the East created a lasting impression on the Crusader knights and they had a profound effect on the cuisine and habits of Europe. Oddly enough trade with the East opened up and the ports of Genoa and Venice in the south and Antwerp and Bruges began to supply the increasing demand for spices. It is interesting in fact, when looking at recipes from recipes from this period in the Medieval age just how highly spiced some of the dishes are. However, Venice's almost exclusive deal with the Arab traders meant that by the thirteenth century almost the entire profits from the European spice trade went to Venice. Yet the Venetian traders wanted a greater slice of the spice pie for themselves and in about 1271 Marco Polo set out overland from Venice across the Crimea in search of the fabled gems and spices of the far east.

Once again spices became an essential part of everyday European life. So much so that 1180 a Pepperers' guild had been established in London that was rapidly transformed into a Spicers' guild. The members of these guilds were in effect the forerunners of apothecaries and spices beceame one of the most important ingredients in the medical practice of the age. This period in history also corresponds with the great Mongol expansion, beginning with the conquests of Genghis Khan (1162–1227). The Mongolian Khans effectively controlled the entirety of the Silk Road and trade with Europe redoubled. Many merchant families (especially from Venice) funded their own caravans to the east and became wealthy on the proceeds. Such a family were the Polos of Venice and in 1271 who travelled with his father Niccòlo and uncle Maffeo (who had previously journeyed to Cathay [China]) with the Pope's response to Kubulai Khan's request for educated people to come and teach Christianity and Western customs to his people. They travelled to Kubulai Khan's court where Marco became a favourite of the Khan and was employed for 17 years. In 1291 Kublai entrusted Marco with his final duty, to escort the Mongol princess Koekecin to her betrothed, the Ilkhan Arghun. They reached the Ilkhanate in 1293 and from there moved to Trabzon where they set sail for Venice. On their return from China in 1295, the family settled in Venice where they became a sensation and attracted crowds of listeners who had difficulties in believing their reports of distant China. Marco Polo was later captured in a minor clash of the war between Venice and Genoa, He spent the few months of his imprisonment, in 1298, dictating to a fellow prisoner, Rustichello da Pisa, a detailed account of his travels in the then-unknown parts of the Far East. This journey became on of the most celebrated early travelogues and became one of the inspirations for the later 'Age of Discovery'.

As well as bringing spices to Europe it is also quite possible that the Spice route brought with it the Black Death that first struck Europe in 1347–1351 CE. Indeed, the disease first seems to have struck China in the mid 1330s and spread along the overland trade routes, first to the Middle East and then Europe. The high mortality of the Black Death caused major social upheaval in the lands which it struck. This led to pressure on the overland trade routes as the Khanate of the Mongols collapsed and various factions vied for dominance across the Arab world. Raiding became rife and the overland routes to the East became unsafe. However, a small amount of spice still managed to find its way into Europe by way of Constantinople. But a resurgent Ottoman Empire was slowly closing-off all the trade routes and by 1453 with the fall of Constantinople the final overland route for spices into Europe was closed off. This effectively left Venice with a virtual monopoly on all spice reaching Europe by the sea routes. So confident were the Egyptians of the Venetian monopoly (they controlled the port of Alexandria from whence the spice reached Venice) that in 1453 they introduced a tariff on all the spices leaving Alexandria that amounted to a third of the total value of the spices.

Obviously, the situation for the remainder of Europe was untenable and the only solution was to find the sea route to the spice lands. This was the impetus for the period in European history that later became known as 'The Age of Discovery'.

The next section in this article deals with the European ages of Discovery and Conquest and how the quest for new sources of spices led to Europeans discovering and attempting to conquer the globe.